Why Sports Science Is Hard to Apply to Individual Triathletes

If you’ve spent any time in triathlon, you’ve probably heard some version of ‘The science says this is optimal’ - Zone 2 volume… HIIT frequency… carbohydrate targets… durability work. But despite better access to sports science than ever before, triathletes will still see wildly different outcomes when applying the same ideas. One athlete thrives while another stagnates and a third breaks down. This isn’t because the science is wrong, it’s because applying population-level research to an individual human organism is far more complex than we often acknowledge.

Sports science studies populations but athletes are individuals.

Sports science tells us what tends to work on average. That’s essential. But averages hide variance, and variance is where real athletes live. Two athletes can complete the same sessions, hit the same numbers and accumulate the same training load, yet diverge completely over time. The issue isn’t compliance or toughness. It’s biology.

Humans are complex adaptive systems

The human body behaves as a complex adaptive system:

multiple interacting subsystems

non-linear responses to stress

constant context-dependent adjustment

Performance, fatigue and durability are not controlled by a single variable like FTP or VO₂max. They emerge from interactions between training load, sleep, energy availability, psychological stress, environment and training history. Metrics are useful but they describe parts of the system, not the system itself.

The body predicts stress, it doesn’t just react to it

A common model of training adaptation is ‘stress → fatigue → recovery → adaptation’. In reality, the body is continuously anticipating future demands. Heart rate rises before hard work begins. Perceived effort reflects how hard the brain expects the task to become, not just what’s happening now. This predictive regulation is an evolved survival feature.

An evolutionary lens on training stress

Humans didn’t evolve to maximise performance metrics. We evolved to survive under uncertainty and energy scarcity. From that perspective:

training stress looks like threat

low energy availability signals danger

chronic stress increases protective responses

When training load stacks on top of poor sleep, low fuelling, life stress, heat or travel, the system becomes conservative. Effort rises, recovery slows, durability declines. This isn’t weakness, it’s protective biology.

Allostasis and allostatic load

Rather than holding fixed set-points the body regulates through allostasis - maintaining stability through continual adjustment. When stress is manageable this leads to adaptation. When stress accumulates across multiple domains the cost of regulation rises. That cumulative cost is known as allostatic load.

In endurance athletes, rising allostatic load often appears as:

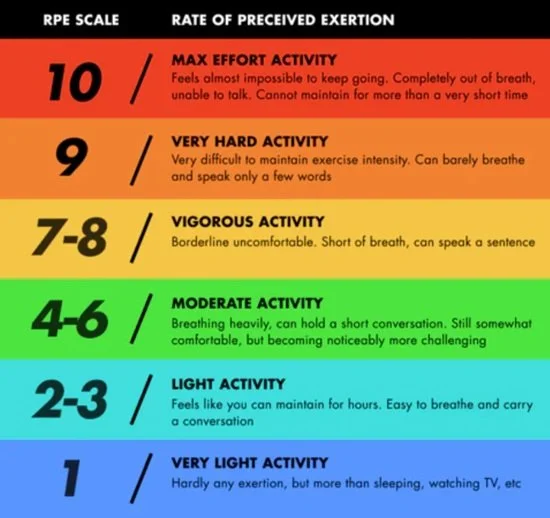

higher RPE at familiar intensities

reduced durability late in sessions

inconsistent performance

illness, niggles or mood changes

At this point, applying more training because it’s ‘optimal’ often backfires. The problem isn’t stimulus, it’s adaptive capacity.

What this means for Triathletes

Sports science remains invaluable, but it must be interpreted rather than blindly applied.

A complexity-aware approach shifts the focus:

from maximising load → managing total stress

from peak metrics → durability and resilience

from rigid plans → responsive adjustment

It explains why RPE is a meaningful signal, why consistency beats hero weeks and why fuelling and recovery often unlock adaptation more reliably than intensity alone.

A reframing, not a rejection

This isn’t an argument against sports science, it’s an argument for how we relate to it as individual athletes.

Research gives us boundaries, probabilities and starting points. But it doesn’t know your history, your stress load, your sleep, your fuelling habits or how your body has learned to respond to exercise over years of training. The mistake many triathletes make is expecting their response to line up neatly with study averages or prescribed predictions. When it doesn’t, they assume something is wrong with them.

In reality, the more appropriate question is rarely ‘Am I doing the science right?’ It’s ‘How is my system responding to this stress?’

That response shows up in durability, perceived effort, consistency, mood, recovery and resilience over time, not just in peak numbers.

Treating yourself as an individual means using sports science as a guide, not a ruler. It means paying attention to patterns in your own responses, respecting when adaptation is happening and recognising when the system is asking for restraint rather than more stimulus. The goal isn’t to force your body to behave like the average participant in a study. It’s to learn how your body adapts, so training becomes a process of observation, adjustment, and trust, not blind expectation.

That shift alone often does more for long-term performance and health than chasing the next supposedly optimal intervention.

Bevan McKinnon / January 2026